Thomas Jefferson by Charles Peale Polk

Thomas Jefferson inherited many slaves. His wife brought a dowry of more than 100 slaves, & he purchased many more throughout his life. At some periods of time, he was one of the largest slaveowners in Virginia. In 1790, Thomas Jefferson gave his newly married daughter & her husband 1000 acres of land & 25 slaves. In 1798, Thomas Jefferson owned 141 slaves, many of them elderly. Two years later he owned 93. When Jefferson's estate was auctioned off at his death, 130 slaves were sold

c 1770: "I made one effort in (the Virginia legislature about 1770) for the permission of the emancipation of slaves, which was rejected: and indeed, during the regal government, nothing liberal could expect success."

1774: "The abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in those colonies (America), where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state. But previous to the enfranchisement of the slaves we have, it is necessary to exclude all further importations from Africa…"

1776: "(King George III) has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought and sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce: and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms against us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.” - from Thomas Jefferson's draft of the Declaration of Independence. This paragraph was voted down by the Congressional Congress.

1778: “I brought a bill to prevent (the slave’s) further importation (to Virginia). This passed without opposition, and stopped the increase of the evil by importation, leaving to future efforts its final eradication.”

1787: “Under the mild treatment our slaves experience, and their wholesome, though coarse food, this blot in our country increases as fast, or faster, than the whites.”

1787: Thomas Jefferson discussed his 1777 bill which, if passed, would have eventually freed the slaves of Virginia & deported them: “It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state…? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousands recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.”

1787: “I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.”

1787: "There must doubtless be an unhappy influence on the manners of our people produced by the existence of slavery among us. The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other... Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation, is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest."

1787: “This unwillingness (to sell slaves) is for their sake, not my own; because my debts once cleared off, I shall try some plan of making their situation happier, determined to content myself with a small portion of their labor.”

1800: “We are truly to be pitied!” Thomas Jefferson’s reaction to Gabriel’s Conspiracy, an attempted slave’s uprising in Virginia.

1807: Thomas Jefferson told an English diplomat that the Blacks were “as far inferior to the rest of mankind as the mule is to the horse, and as made to carry burdens.”

1807: The Constitution said Congress could not ban the slave trade (that is, importing slaves into the country) until 1808. In March of 1807 Thomas Jefferson recommended, and Congress enacted, such a law to take effect January 1, 1808.

c 1814: “The amalgamation of whites with blacks produces a degradation to which no lover of his country, no lover of excellence in the human character, can innocently consent.”

1815: “The slave is to be prepared by instruction and habit for self-government, and for the honest pursuits of industry and social duty. The former must precede the latter.”

1820: (Discussing slavery) “We have the wolf by the ears and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale and self-preservation in the other.”

1821: “Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people (slaves) are to be free. Nor is it less certain that the two races, equally free, cannot live in the same government. Nature, habit, opinion has drawn indelible lines of distinction between them.”

1824: Thomas Jefferson discussed his continuing hope that the slaves can be sent to Africa: “To send off the whole of these at once, nobody conceives to be practicable for us, or expedient for them. Let us take twenty-five years for its accomplishment, within which time they will be doubled. Their estimated value as property…must be paid or lost by somebody.”

Friday, May 31, 2019

President Thomas Jefferson & Slavery

Wednesday, May 29, 2019

Ex-slave Angeline Lester, about 90, Ohio, Remembers being told she was free in 19C America

Angeline related that after the war a celebration was held in Benevolence. Georgia; and Angeline said it was here she first tested a roasted piece of meat...The following Sunday, the negroes were called to their master's house where they were told they were free, and those who wished, could go, and the others could stay and he would pay them a fair wage, but if they left they could take only the clothing on their back.

Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. Photo from 20th century.

Tuesday, May 28, 2019

Free Black Men and Women in Maryland

Mrs. Juliann Jane Tillman, Free Black Female Preacher of the A.M.E. Church / from life by A. Hoffy ; printed by P.S. Duval.

From the 17C to the 19C, there was a growing free black population in Maryland. This population grew quickly in the antebellum years. African Americans were usually emancipated for diligent work, good conduct, familial connections, or commendable service. At other times white owners experienced a change of heart, an attack of conscience, or, in the case of Quaker meetings, freed their slaves in following their religion.

The methods for manumission in Maryland included court actions, instructions in owners' wills, self-purchase, purchase of one's own family member's freedom with money earned when hired out, governmental decrees, or rewards for military service. In Maryland, according to acts of 1697 and 1692, the law declared that children followed the condition of their mother. Thus, when children were born to a free mother, they were free also.

In 1752, the population of Baltimore County included 166 mulatto slaves, 96 free mulattoes, 4,027 black slaves and eight free blacks. The census of 1790 recorded that about eight thousand free blacks lived in the state at that time. The free black population was concentrated in northern and western Maryland.

In 1830, the free black population was just under 53,000, about 12 percent of Maryland's population, according to the U.S. Census. That meant that about one-third of the entire Maryland African American population in Maryland was free.

Free blacks generally were not accorded the same privileges as white citizens. Maryland changed its laws relating to free blacks depending on the political climate. For a brief period some free blacks had the right to vote, but the law was later rescinded. Blacks could not carry firearms or testify against whites in court.

Free blacks—especially children—lived under the threat of being beaten or kidnapped by whites who would sell them into slavery. One reason whites formed the Maryland Abolition Society was to try to protect free blacks from kidnappers. Maryland passed and repealed several laws prohibiting blacks from assembling or carrying firearms. Maryland county governments often vacillated about the right of free blacks to hold and bequeath property. Whites often sought to restrict the type of work blacks could do because they did not want to compete with them. At various times the Maryland Assembly tried to pass laws prohibiting blacks from reading abolitionist literature, operating boats, obtaining licenses for pedaling, participating in certain trades, or having or driving hacks, carts or drays. There was also an effort keep free blacks from owning dogs. Slaveholders' motive for many of the laws, particularly those prohibiting free blacks from owning conveyances, was to prevent them from aiding runaway slaves.

In spite of numerous restrictions, free blacks in Maryland formed their own churches, schools, benevolent societies, and businesses. By 1847 there were at least thirteen black churches in Baltimore alone. Many churches were a part of larger denominations which met periodically in various states to discuss both religious and political matters.

The 1850 Census indicates that over 50 percent of Maryland free blacks could read and/or write. Free persons of color worked as domestics, small farmers, innkeepers, street vendors, ship caulkers, stevedores, sailors and boatmen, draymen, barbers, teamsters, blacksmiths, and liverymen. Blacks who had purchased their freedom were usually able to do so because they had earned money with their skilled labor.

Some free blacks, like astronomer Benjamin Banneker and preacher Daniel Coker, were able to record their own experiences. Banneker published an almanac and aided in the survey of the Federal District, later to become the District of Columbia. Coker became one of the first emigrants to return to Africa with the American Colonization Society.

From the 17C to the 19C, there was a growing free black population in Maryland. This population grew quickly in the antebellum years. African Americans were usually emancipated for diligent work, good conduct, familial connections, or commendable service. At other times white owners experienced a change of heart, an attack of conscience, or, in the case of Quaker meetings, freed their slaves in following their religion.

The methods for manumission in Maryland included court actions, instructions in owners' wills, self-purchase, purchase of one's own family member's freedom with money earned when hired out, governmental decrees, or rewards for military service. In Maryland, according to acts of 1697 and 1692, the law declared that children followed the condition of their mother. Thus, when children were born to a free mother, they were free also.

In 1752, the population of Baltimore County included 166 mulatto slaves, 96 free mulattoes, 4,027 black slaves and eight free blacks. The census of 1790 recorded that about eight thousand free blacks lived in the state at that time. The free black population was concentrated in northern and western Maryland.

In 1830, the free black population was just under 53,000, about 12 percent of Maryland's population, according to the U.S. Census. That meant that about one-third of the entire Maryland African American population in Maryland was free.

Free blacks generally were not accorded the same privileges as white citizens. Maryland changed its laws relating to free blacks depending on the political climate. For a brief period some free blacks had the right to vote, but the law was later rescinded. Blacks could not carry firearms or testify against whites in court.

Free blacks—especially children—lived under the threat of being beaten or kidnapped by whites who would sell them into slavery. One reason whites formed the Maryland Abolition Society was to try to protect free blacks from kidnappers. Maryland passed and repealed several laws prohibiting blacks from assembling or carrying firearms. Maryland county governments often vacillated about the right of free blacks to hold and bequeath property. Whites often sought to restrict the type of work blacks could do because they did not want to compete with them. At various times the Maryland Assembly tried to pass laws prohibiting blacks from reading abolitionist literature, operating boats, obtaining licenses for pedaling, participating in certain trades, or having or driving hacks, carts or drays. There was also an effort keep free blacks from owning dogs. Slaveholders' motive for many of the laws, particularly those prohibiting free blacks from owning conveyances, was to prevent them from aiding runaway slaves.

In spite of numerous restrictions, free blacks in Maryland formed their own churches, schools, benevolent societies, and businesses. By 1847 there were at least thirteen black churches in Baltimore alone. Many churches were a part of larger denominations which met periodically in various states to discuss both religious and political matters.

The 1850 Census indicates that over 50 percent of Maryland free blacks could read and/or write. Free persons of color worked as domestics, small farmers, innkeepers, street vendors, ship caulkers, stevedores, sailors and boatmen, draymen, barbers, teamsters, blacksmiths, and liverymen. Blacks who had purchased their freedom were usually able to do so because they had earned money with their skilled labor.

Some free blacks, like astronomer Benjamin Banneker and preacher Daniel Coker, were able to record their own experiences. Banneker published an almanac and aided in the survey of the Federal District, later to become the District of Columbia. Coker became one of the first emigrants to return to Africa with the American Colonization Society.

Monday, May 27, 2019

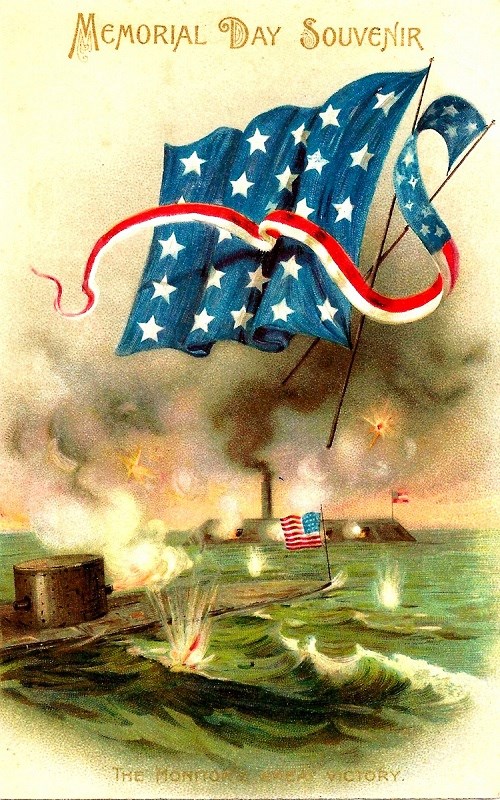

19C Memorial Day - Decoration Day Posrcards

Thomas Nast (1840-1902) looks at Memorial Day

Thomas Nast (1840-1902) Harpers Weekly Decoration Day, May 30, 1871

Thomas Nast (1840-1902) in Harpers Weekly

Thomas Nast (1840-1902) in Harpers Weekly

Thomas Nast (1840-1902) in Harpers Weekly

Thomas Nast (1840-1902) in Harpers Weekly

Harper's Weekly looks at Memorial Day

Decorating 3,000 Graves of Civil War casualties at Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York from Harper's Weekly

Charles S. Reinhart Illustration, Harper's Weekly June 4, 1870 Floral Tribute to the Nation's Dead

Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York 1869 Decoration Day

Harper's Weekly 1873. Decoration Day

Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia Decorating Graves of the Fallen

Harper's Weekley Decorating the Graves of Civil War Soldiers

Charles S. Reinhart Illustration, Harper's Weekly June 4, 1870 Floral Tribute to the Nation's Dead

Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York 1869 Decoration Day

Harper's Weekly 1873. Decoration Day

Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia Decorating Graves of the Fallen

Harper's Weekley Decorating the Graves of Civil War Soldiers

Sunday, May 26, 2019

19C Newspaper Woman Anne Newport Royal 1769-1854

From A Centennial History of Alleghany County, Virginia by Oren F. Morton. Published in 1896.

"Anne Newport was born near Baltimore in 1769. In 1772 her parents had moved to the mouth of the Loyal Hanna in the west of Pennsylvania. There the family lived in a log cabin only eight feet broad & ten feet long. It contained a bed, a puncheon table, & four stools, but there was neither a trunk nor a box, nor was there a tablecloth in the hut. Anne never saw a metallic pin until she was a grown woman. On the frontier thorns were used as pins & mussel-shells as spoons. But in possessing knives, forks, & spoons, the Newports were better off than most of their neighbors.

"From the door could be seen a tree in which was the nest of an eagle.

"Mr. Newport died before Anne was grown, & the widow married a man named Butler. An Indian raid in 1782 made her a widow a second time, & three years later she was at Staunton, Virginia, near which town she seems to have had relatives.

"To find relief from a skin ailment, Mrs. Butler went with her children to Sweet Springs. Major William Royall, a well educated but reclusive local luminary & a zealous patriot of the American Revolution, invited her to become his housekeeper, & she accepted. Anne seems to have interested the old planter at once. She had a bright, retentive mind.

"In 1797 the hermit-philosopher & the forest-bred girl were married. Their sixteen years of wedded life were childless but happy. The wife idolized her husband & his views were her views. Whenever the district court sat at Sweet Springs the house was full of guests. Toward the end of his life Royall was an invalid & was tenderly nursed. He died in 1813, making his wife & a nephew his executors. With the exception of one tract of land, he left his wife during her widowhood the use of all his estate. The will was at once disputed by another nephew & ten years of litigation followed. The relatives of Royall would not accept the widow as a social equal. They even denied that there had been any marriage, but this contention was overthrown by the courts.

"Mrs. Royall was now quite alone. For a time books lost their charm & she had a great desire to see the world. It was doubtless the persecution by the relatives of Royall that made her say she could not love the mountains any longer. Yet it was an article in her creed that “one learns more in a day by mixing with mankind than he can in a year shut up in a closet.”

"She sold a house & two lots & began her travels. From 1817 to 1825 she was much of the time in the South, especially in Alabama, for which state she had a liking. It was while she was there that the lawsuit was decided against her. She was dispossessed of her inheritance & even jailed as an imposter. The shock made her ill & to relieve her mind she began writing her first book. Yet she did not let this work interfere with going to Washington to secure the pension, to which as a widow, she was entitled.

"Mrs. Royall’s first visit to the national capital was in July, 1824. The first statesman she met was John Quincy Adams, who paid her five dollars for an advance subscription, asked her to call on Mrs. Adams, & promised his aid in securing a pension. This promise he faithfully observed. She spent six weeks in Washington, & then journeyed to New England to collect further material for her book & to secure more advance orders. Under the title of Sketches of history, life, & manners in the United States., her first book was published at Hartford, Connecticut under the pseudonym A Traveller.

"During the next five years Mrs. Royall visited nearly every town of consequence in the twenty-four states which then existed. Meanwhile she wrote a novel, The Tennessean, & nine more volumes of descriptive sketches. This prosperous period was brought to a close by the enemies her writings had created. Through a forced interpretation of a moss-covered law, Mrs. Royall was convicted of being a common scold, fined ten dollars, & bound over for one year. She was the first woman in America to be subjected to such an indignity. She would have retired to a farm, but had no means to purchase one. A trip South in 1830 yielded meager returns in a financial way, & on her return she was nearly worn out.

"In 1831, Mrs. Royall took up her residence in the city of Washington, then a straggling town of cheap houses, muddy streets, unhealthful marshes, & perhaps 15,000 inhabitants. The national capital was her home for the remainder of her life. For the greater portion of this time she lived in a rented house standing in the northeast corner of the present grounds of the Library of Congress. There were shade trees in the yard & a good well. Then as now, the city covered a large surface & the widow could keep poultry. One day Richard M. Johnson, while vice-president, helped her catch a hen as he was passing the house.

"Mrs. Royal was now sixty-two years of age. To keep the wolf from the door she set up a printing press in her own house, taking out a sink to make room for it. As sole editor & proprietor, she began the publication of a weekly newspaper. Her choice of title was not a good one. The name, Paul Pry, is calculated to make one think it was a yellow sheet, devoted to sensation & scandal. On the contrary, it was clean. The first issue appeared December 3, 1831. The first page was given to literary articles, the second & third to editorials, news, jokes, & miscellaneous matter, & the fourth to advertisements. In 1837 the title was changed to The Huntress. In the new form the paper was a distinct improvement, though less a financial success, owing to the antagonism of Calvinistic Protestants. Nevertheless, Mrs. Royall continued its publication until July 2, 1854, her death taking place three months later at the age of eighty-five.

"In personal appearance Mrs. Royall was short & very plump. She had pink cheeks, fair hair, very bright blue eyes, & in her dress she was scrupulously neat. She was a good talker, was quick to laugh, & had a keen sense of the ridiculous. She was loyal to her friends, & young men admired her for her courage & her aptness in repartee.

"Anne Royal was broad & intense in her patriotism, & she fervently desired the preservation of the Federal government. She was proud that the United States extends to the Pacific. She was enthusiastic over the Great West. She admired New England, where her books sold well. The people of New York she found immersed in business & lacking in refinement, & yet less aristocratic than those of Pennsylvania & the South. For the east of Virginia she had little liking, probably because her husband had turned his back upon it. With respect to slavery she was tolerant, & yet she did not think well of the institution. Major Royall was a slaveholder, but emancipated a boy.

"Her newspaper was a free lance in a political way, & wielded an influence not to be despised. The things it stood for were usually those that make for social betterment. She was quick to detect graft & political schemes. On one occasion she was offered $1,000 if she would keep silent on a certain matter. She replied that she was not for sale.

"Her personal knowledge of the public men of her time is most remarkable. She met & talked with every person who filled the presidential chair, beginning with Washington & ending with Lincoln. It was probably on the occasion of his visit to Sweet Springs in 1797 that she saw General Washington. She chatted with John Adams in his own home when he was eighty-nine years of age. Lincoln she must have seen during his one term in Congress. She even met Lafayette on his visit to Boston in 1825. The great Frenchman gave her a letter in support of her pension claim.

"During her widowhood Mrs. Royall was very poor, & yet she was always generous. That she managed to travel so much is rather surprising. But when she made up her mind to go anywhere, she set out, & she managed to accomplish her purpose. Her husband was a freemason, & he had told her not to hesitate to call on the brethren of the mystic tie when help was necessary. She never called on them in vain. The Catholics & the Jews also showed her much kindness.

"But Mrs. Royall was her own worst enemy. She did not mince her words at any time, & often they stung like a hornet. Her pen was caustic, because she had no patience with sidestepping & subterfuge on questions clear to herself & which she earnestly believed to be for the good of the public. It was the public men she flayed without mercy who were the means of keeping her out of a pension until she was more than eighty years old. Yet she never gave up the fight & was finally granted $40 a month."

"From the door could be seen a tree in which was the nest of an eagle.

"Mr. Newport died before Anne was grown, & the widow married a man named Butler. An Indian raid in 1782 made her a widow a second time, & three years later she was at Staunton, Virginia, near which town she seems to have had relatives.

"To find relief from a skin ailment, Mrs. Butler went with her children to Sweet Springs. Major William Royall, a well educated but reclusive local luminary & a zealous patriot of the American Revolution, invited her to become his housekeeper, & she accepted. Anne seems to have interested the old planter at once. She had a bright, retentive mind.

"In 1797 the hermit-philosopher & the forest-bred girl were married. Their sixteen years of wedded life were childless but happy. The wife idolized her husband & his views were her views. Whenever the district court sat at Sweet Springs the house was full of guests. Toward the end of his life Royall was an invalid & was tenderly nursed. He died in 1813, making his wife & a nephew his executors. With the exception of one tract of land, he left his wife during her widowhood the use of all his estate. The will was at once disputed by another nephew & ten years of litigation followed. The relatives of Royall would not accept the widow as a social equal. They even denied that there had been any marriage, but this contention was overthrown by the courts.

"Mrs. Royall was now quite alone. For a time books lost their charm & she had a great desire to see the world. It was doubtless the persecution by the relatives of Royall that made her say she could not love the mountains any longer. Yet it was an article in her creed that “one learns more in a day by mixing with mankind than he can in a year shut up in a closet.”

"She sold a house & two lots & began her travels. From 1817 to 1825 she was much of the time in the South, especially in Alabama, for which state she had a liking. It was while she was there that the lawsuit was decided against her. She was dispossessed of her inheritance & even jailed as an imposter. The shock made her ill & to relieve her mind she began writing her first book. Yet she did not let this work interfere with going to Washington to secure the pension, to which as a widow, she was entitled.

"Mrs. Royall’s first visit to the national capital was in July, 1824. The first statesman she met was John Quincy Adams, who paid her five dollars for an advance subscription, asked her to call on Mrs. Adams, & promised his aid in securing a pension. This promise he faithfully observed. She spent six weeks in Washington, & then journeyed to New England to collect further material for her book & to secure more advance orders. Under the title of Sketches of history, life, & manners in the United States., her first book was published at Hartford, Connecticut under the pseudonym A Traveller.

"During the next five years Mrs. Royall visited nearly every town of consequence in the twenty-four states which then existed. Meanwhile she wrote a novel, The Tennessean, & nine more volumes of descriptive sketches. This prosperous period was brought to a close by the enemies her writings had created. Through a forced interpretation of a moss-covered law, Mrs. Royall was convicted of being a common scold, fined ten dollars, & bound over for one year. She was the first woman in America to be subjected to such an indignity. She would have retired to a farm, but had no means to purchase one. A trip South in 1830 yielded meager returns in a financial way, & on her return she was nearly worn out.

"In 1831, Mrs. Royall took up her residence in the city of Washington, then a straggling town of cheap houses, muddy streets, unhealthful marshes, & perhaps 15,000 inhabitants. The national capital was her home for the remainder of her life. For the greater portion of this time she lived in a rented house standing in the northeast corner of the present grounds of the Library of Congress. There were shade trees in the yard & a good well. Then as now, the city covered a large surface & the widow could keep poultry. One day Richard M. Johnson, while vice-president, helped her catch a hen as he was passing the house.

"Mrs. Royal was now sixty-two years of age. To keep the wolf from the door she set up a printing press in her own house, taking out a sink to make room for it. As sole editor & proprietor, she began the publication of a weekly newspaper. Her choice of title was not a good one. The name, Paul Pry, is calculated to make one think it was a yellow sheet, devoted to sensation & scandal. On the contrary, it was clean. The first issue appeared December 3, 1831. The first page was given to literary articles, the second & third to editorials, news, jokes, & miscellaneous matter, & the fourth to advertisements. In 1837 the title was changed to The Huntress. In the new form the paper was a distinct improvement, though less a financial success, owing to the antagonism of Calvinistic Protestants. Nevertheless, Mrs. Royall continued its publication until July 2, 1854, her death taking place three months later at the age of eighty-five.

"In personal appearance Mrs. Royall was short & very plump. She had pink cheeks, fair hair, very bright blue eyes, & in her dress she was scrupulously neat. She was a good talker, was quick to laugh, & had a keen sense of the ridiculous. She was loyal to her friends, & young men admired her for her courage & her aptness in repartee.

"Anne Royal was broad & intense in her patriotism, & she fervently desired the preservation of the Federal government. She was proud that the United States extends to the Pacific. She was enthusiastic over the Great West. She admired New England, where her books sold well. The people of New York she found immersed in business & lacking in refinement, & yet less aristocratic than those of Pennsylvania & the South. For the east of Virginia she had little liking, probably because her husband had turned his back upon it. With respect to slavery she was tolerant, & yet she did not think well of the institution. Major Royall was a slaveholder, but emancipated a boy.

"Her newspaper was a free lance in a political way, & wielded an influence not to be despised. The things it stood for were usually those that make for social betterment. She was quick to detect graft & political schemes. On one occasion she was offered $1,000 if she would keep silent on a certain matter. She replied that she was not for sale.

"Her personal knowledge of the public men of her time is most remarkable. She met & talked with every person who filled the presidential chair, beginning with Washington & ending with Lincoln. It was probably on the occasion of his visit to Sweet Springs in 1797 that she saw General Washington. She chatted with John Adams in his own home when he was eighty-nine years of age. Lincoln she must have seen during his one term in Congress. She even met Lafayette on his visit to Boston in 1825. The great Frenchman gave her a letter in support of her pension claim.

"During her widowhood Mrs. Royall was very poor, & yet she was always generous. That she managed to travel so much is rather surprising. But when she made up her mind to go anywhere, she set out, & she managed to accomplish her purpose. Her husband was a freemason, & he had told her not to hesitate to call on the brethren of the mystic tie when help was necessary. She never called on them in vain. The Catholics & the Jews also showed her much kindness.

"But Mrs. Royall was her own worst enemy. She did not mince her words at any time, & often they stung like a hornet. Her pen was caustic, because she had no patience with sidestepping & subterfuge on questions clear to herself & which she earnestly believed to be for the good of the public. It was the public men she flayed without mercy who were the means of keeping her out of a pension until she was more than eighty years old. Yet she never gave up the fight & was finally granted $40 a month."

Friday, May 24, 2019

Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks(1752-1837) Virginia Herbal Doctor

Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks(1752-1837) Virginia Planter & Herbal Doctor 1752 - 1837 Collection of the University of Virginia Art Museum. Painted by John Toole, 1815-1860.

Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks made an indirect but important contribution to the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s outcome. Meriwether Lewis’s extensive knowledge of herbs, wild plants and their medicinal properties led her to be renowned for her herbal doctoring. And she passed what she knew along to her son. She encouraged young Meriwether’s interest in plants and wildlife.

Lucy Thornton Meriwether was born in Albemarle County on February 4, 1752. She was the daughter of Col. Thomas and Elizabeth Thornton Meriwether. Thomas Meriwether's (1714-1756) home was at “Clover Fields." Thomas continued to purchase land to add to the land gifted to him by his grandfather, until his total land holdings were 9,000 acres spread over several estates. He married Elizabeth Thornton in 1735 and that same year, “he had 11 slaves, 2 horses, a plow and farm implements, 18 head of cattle and over 100 hogs, sows and pigs on his Totier Creek property. His wife, Elizabeth Thornton (1717-1794). Together, they had 11 children. Following her husband’s death, Elizabeth married Robert Lewis of “Belvoir” who later became Lucy’s father-in-law as well as her step-father.

In 1768 or 1769, when Lucy was either 16 or 17, she married her step-brother and first cousin-once-removed 35 year old William Lewis. William Lewis (1735 - 1779) had grown up in great prosperity as his father owned 21,600 acres in the Albemarle County area as well as an interest in 100,000 acres in Greenbrier County (now West Virginia. Upon his father’s death in 1765, William Lewis inherited “Locust Hill” and 1,896 acres on Ivy Creek (600 of which he later sold) and the slaves to work it. He probably built the house during the 3 years between his inheritance and his marriage.William Lewis was a lieutenant in the Virginia militia and served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution.* Thus, like many of the men in Lucy’s family, he was away from home for long periods, leaving Lucy to manage his plantation of over 1,600 acres. William Lewis died in the autumn of 1779. On his way home from army duty, he crossed the Rivanna River when it was in flood and his horse was swept away and drowned. He swam ashore and managed to get to “Clover Fields”, the Meriwether family home, but as a result of the ordeal, he came down with a bad chill and died of pneumonia. He was buried at “Clover Fields.”

Within six months after her husband’s death, Lucy Meriwether Lewis married Capt. John Marks (1740 – 1791) on May 13, 1780. A number of planters from Albemarle County, including John Marks, Francis Meriwether, Benjamin Taliaferro and Thomas Gilmer immigrated to land along the Broad River in Wilkes County, Georgia in 1784. In 1791, John Marks died of causes unknown, and Lucy became a widow for the 2nd time. Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks gave birth to Jane Meriwether Lewis, Meriwether Lewis, Lucinda Lewis (who died in childhood) and Reuben Lewis while married to William Lewis and John Marks and Mary Garland Marks while married to Captain John Marks. Both Reuben and John (II) grew up to become doctors. She was 39 years old decided to return to “Locust Hill.”

Lucy was locally famous as a “yarb” or herb doctor. Lucy’s type of doctoring was called “Empiric” and based on practical experience. She was folk practitioner – a job often filled by women. She traveled throughout Albemarle County by horseback caring for the sick well into her early eighties. Perhaps she learned medicine from her father, also known as a healer, and her brother Francis, who was a “Regular” or formally-trained doctor. Lucy may have grown medicinal plants in her garden at “Locust Hill” and collected them in the wild as well. Her famous son, Meriwether Lewis, relied on the skills he had learned from his mother when he treated himself and others on the Lewis and Clark expedition. Lucy remained active in her doctoring into her eighties, according to family accounts, even in old age, she continued to ride on horseback around the countryside visiting the sick, both slave and free.

Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks made an indirect but important contribution to the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s outcome. Meriwether Lewis’s extensive knowledge of herbs, wild plants and their medicinal properties led her to be renowned for her herbal doctoring. And she passed what she knew along to her son. She encouraged young Meriwether’s interest in plants and wildlife.

Lucy Thornton Meriwether was born in Albemarle County on February 4, 1752. She was the daughter of Col. Thomas and Elizabeth Thornton Meriwether. Thomas Meriwether's (1714-1756) home was at “Clover Fields." Thomas continued to purchase land to add to the land gifted to him by his grandfather, until his total land holdings were 9,000 acres spread over several estates. He married Elizabeth Thornton in 1735 and that same year, “he had 11 slaves, 2 horses, a plow and farm implements, 18 head of cattle and over 100 hogs, sows and pigs on his Totier Creek property. His wife, Elizabeth Thornton (1717-1794). Together, they had 11 children. Following her husband’s death, Elizabeth married Robert Lewis of “Belvoir” who later became Lucy’s father-in-law as well as her step-father.

In 1768 or 1769, when Lucy was either 16 or 17, she married her step-brother and first cousin-once-removed 35 year old William Lewis. William Lewis (1735 - 1779) had grown up in great prosperity as his father owned 21,600 acres in the Albemarle County area as well as an interest in 100,000 acres in Greenbrier County (now West Virginia. Upon his father’s death in 1765, William Lewis inherited “Locust Hill” and 1,896 acres on Ivy Creek (600 of which he later sold) and the slaves to work it. He probably built the house during the 3 years between his inheritance and his marriage.William Lewis was a lieutenant in the Virginia militia and served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution.* Thus, like many of the men in Lucy’s family, he was away from home for long periods, leaving Lucy to manage his plantation of over 1,600 acres. William Lewis died in the autumn of 1779. On his way home from army duty, he crossed the Rivanna River when it was in flood and his horse was swept away and drowned. He swam ashore and managed to get to “Clover Fields”, the Meriwether family home, but as a result of the ordeal, he came down with a bad chill and died of pneumonia. He was buried at “Clover Fields.”

Within six months after her husband’s death, Lucy Meriwether Lewis married Capt. John Marks (1740 – 1791) on May 13, 1780. A number of planters from Albemarle County, including John Marks, Francis Meriwether, Benjamin Taliaferro and Thomas Gilmer immigrated to land along the Broad River in Wilkes County, Georgia in 1784. In 1791, John Marks died of causes unknown, and Lucy became a widow for the 2nd time. Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks gave birth to Jane Meriwether Lewis, Meriwether Lewis, Lucinda Lewis (who died in childhood) and Reuben Lewis while married to William Lewis and John Marks and Mary Garland Marks while married to Captain John Marks. Both Reuben and John (II) grew up to become doctors. She was 39 years old decided to return to “Locust Hill.”

Lucy was locally famous as a “yarb” or herb doctor. Lucy’s type of doctoring was called “Empiric” and based on practical experience. She was folk practitioner – a job often filled by women. She traveled throughout Albemarle County by horseback caring for the sick well into her early eighties. Perhaps she learned medicine from her father, also known as a healer, and her brother Francis, who was a “Regular” or formally-trained doctor. Lucy may have grown medicinal plants in her garden at “Locust Hill” and collected them in the wild as well. Her famous son, Meriwether Lewis, relied on the skills he had learned from his mother when he treated himself and others on the Lewis and Clark expedition. Lucy remained active in her doctoring into her eighties, according to family accounts, even in old age, she continued to ride on horseback around the countryside visiting the sick, both slave and free.

Thursday, May 23, 2019

Ex-slave Cindy Washington, about 80, Remembers going to church with the white folks in 19C America

Cindy remembered, "...we was taught to read an' write, but mos' of de slaves didn't want to learn. Us little niggers would hide our books under de steps to keep f'um havin' to study. Us'd go to church wid de white folks on Sunday and sit in de back, an' den we go home an' eat a big Sunday meal."

Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. Photo from 20th century.

Wednesday, May 22, 2019

Child in the Lap of her Nurse

CHILD ASLEEP IN LAP OF NURSE by Mary Lyde Hicks Williams. Mary Lyde Hicks Williams (1866-1959) Mary's paintings of freed slaves reflected daily life she saw on her uncle's plantation during Reconstruction in North Carolina.

Tuesday, May 21, 2019

Ex-slave Fannie Brown Remembers dancing to fiddle music in 19C America

Fannie recounted, "My how dem niggers could play a fiddle back in de good ole days. On de moon-light nights, us uset to dance by de light ob de moon under a big oak tree 'till mos' time to go to work de nex' mornin'. One time de bes' fiddler in de country was playin' fer us to dance, an' he broke a string. It was too fur to go to Austin to git anodder, so he jus' played on widout de string what broke an' de tune sounded more like a squeech owl dan eny thing, but us danced jus de same."

Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. Photo from 20th century.

Sunday, May 19, 2019

Women on the North American Canadian Frontier in 19C - by Dutch-born Cornelius Krieghoff 1815-1872

Cornelius Krieghoff (Dutch-born Canadian painter, 1815-1872) Ice Bridge at Longue Point 1847

Cornelius Krieghoff 1815-1872 was born in Amsterdam, spent his formative years in Bavaria, & studied in Rotterdam & Dusseldorf. He traveled to the United States in the 1830s, where he served in the Army for a few years. He married a young woman from Quebec & moved to the Montreal area, where he painted genre paintings of the people & countryside of Canada. According to Charles C. Hill, Curator of Canadian Art at the National Gallery, "Krieghoff was the first Canadian artist to interpret in oils... the splendour of our waterfalls, & the hardships & daily life of people living on the edge of new frontiers" Krieghoff moved to Quebec from 1854-1863, before he came to Chicago to live with his daughter.

Labels:

19C,

Months/Seasons/Weather/Time,

Native Americans/Indigenous Peoples/Westward Expansion,

US Art,

US History

Saturday, May 18, 2019

Ironing before a Log Fire

1890-1910 After Slavery - Ironing before a Log Fire by North Carolinian Mary Lyde Hicks Williams. Mary Lyde Hicks Williams (1866-1959) Mary's paintings of freed slaves reflected daily life she saw on her uncle's plantation during Reconstruction in North Carolina.

Friday, May 17, 2019

Ex-slave Leithean Spinks, about 82, Remembers her bossy 1st husband in 19C America

Leithean remembered her first marriage, "Ise gits mai'ied in 1872 to Sol Pleasant. Weuns have 2 chilluns befo' weuns sep'rated in 1876. De trouble am he wants to be de boss of de job an' let me do de wo'k. 'Twarnt long 'til Ise 'cides Ise don't need a boss, so Ise transpo'ted him. Ise told him, 'Nigger, git outer heah, an' don't never come back. If yous come back, Ise smack yous down.' Ise never see him after dat."

Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. Photo from 20th century.

Thursday, May 16, 2019

Churning and Dish Washing

Churning and Dish Washing by Mary Lyde Hicks Williams. Mary Lyde Hicks Williams (1866-1959) Mary's paintings of freed slaves reflected daily life she saw on her uncle's plantation during Reconstruction in North Carolina.

Wednesday, May 15, 2019

Finding her mother after she was freed in 19C America

Mary remembered, "...when the war was over, I started out an' looked for mamma again, an' found her like they said in Wharton County near where Wharton is. Law me, talk 'bout cryin' an' singin' an' cryin' some more, we sure done it. I stayed with mamma an' we worked right there 'til I gets married in 1871 to John Armstrong an' then we all comes to Houston."

Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. Photo from 20th century.

Monday, May 13, 2019

Fighting for Equality & Bloomers - Amelia Jenks Bloomer 1818-1894

Amelia Bloomer edited the first American newspaper for women, The Lily. It was issued from 1849 until 1853. The newspaper began as a temperance journal. Bloomer felt that as women lecturers were considered unseemly, writing was the best way for women to work for reform. Originally, The Lily was to be for “home distribution” among members of the Seneca Falls Ladies Temperance Society, which had formed in 1848.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s cousin Elizabeth Smith Miller introduced the outfit and editor Amelia Bloomer publicized it in The Lily.

Like most local endeavors, the paper encountered several obstacles early on, and the Society’s enthusiasm died out. Bloomer felt a commitment to publish and assumed full responsibility for editing and publishing the paper. Originally, the title page had the legend “Published by a committee of ladies.” But after 1850 – only Bloomer’s name appeared on the masthead.

1851 Currier and IvesAlthough women’s exclusion from membership in temperance societies and other reform activities was the main force that moved the Ladies Temperance Society to publish The Lily, it was not at first a radical paper. Its editorial stance conformed to the emerging stereotype of women as “defenders of the home.”

Photo c 1855

In the first issue, Bloomer wrote: It is woman that speaks through The Lily…Intemperance is the great foe to her peace and happiness. It is that above all that has made her Home desolate and beggared her offspring…. Surely, she has the right to wield her pen for its Suppression. Surely, she may without throwing aside the modest refinements which so much become her sex, use her influence to lead her fellow mortals from the destroyer’s path. The Lily always maintained its focus on temperance. Fillers often told horror stories about the effects of alcohol. For example, the May 1849 issue noted, “A man when drunk fell into a kettle of boiling brine at Liverpool, Onondaga Co. and was scaled to death.” But gradually, the newspaper began to include articles about other subjects of interest to women. Many were from the pen of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, writing under the pseudonym “sunflower.” The earliest Stanton’s articles dealt with the temperance, child-bearing, and education, but she soon turned to the issue of women’s rights. She wrote about laws unfair to women and demanded change.

Bloomer was greatly influenced by Stanton and gradually became a convert to the cause of women’s rights. Recalling the case of an elderly friend who was turned out of her home when her husband died without a will she wrote: Later, other similar cases coming to my knowledge made me familiar with cruelty of the laws towards women; and when the women rights convention put forth its Declaration of Sentiments. I was ready to join with that party in demanding for women such change in laws as would give her a right to her earnings, and her children a right to wider fields of employment and a better education, and also a right to protect her interest at the ballot box.

Bloomer became interested in dress reform, advocating that women wear the outfit that came to be known as the “Bloomer costume.” Actually the reform of clothing for women began in the 1850s, as a result of the need for a more practical way of dressing . The reform started in New England where the social activist Elizabeth Smith Miller (1822-1911), called Libby Miller. Mrs Miller was the daughter of abolitionists Gerrit Smith and his second wife, Ann Carroll Fitzhugh. She was a lifelong of the women's rights movement. She became famous when she adopted what she considered a more rational costume: Turk trousers - loose trousers gathered at the ankles like the trousers worn by Middle Eastern and Central Asian women – worn under a short dress or knee length skirt. The outfits were similar to the clothing worn by the women in the Oneida Community, a religious commune founded by John Humphrey Noyes in Oneida, New York in 1848.

This new fashion was soon supported by Bloomer, by then a women's rights and temperance advocate. Bloomer popularized Mr Miller’s idea in her bi-weekly publication The Lily. And this women's clothing reform soon was named bloomers. The rebellion against the voluminous and constraining fashion of the Victorian period was both a practical necessity and a focal point of social reform. Stanton and others copied a knee-length dress with pants worn by Elizabeth Smith Miller of Geneva, New York.

For some time the "Bloomer" outfit was worn by many of the leaders in the women's rights movement, then it was abandoned because of the heavy criticism in the popular press. In 1859, Amelia Bloomer herself said that a new invention, the crinoline, was a sufficient reform. The bloomer costume returned later, adapted and modified, as a women's athletic costume in the 1890s and early 1900s.

1864 Godey's Lady's Book

Although Bloomer refused to take any credit for inventing the pants-and-tunic outfit, her name became associated with it because she wrote articles about the unusual dress, printed illustrations in The Lily, and wore the costume herself. In reference to her advocacy of the costume, she once wrote, “I stood amazed at the furor I had unwittingly caused.” But people certainly were interested in the new fashion. She remembered: “As soon as it became known that I was wearing the new dress, letters came pouring in upon me by the hundreds from women all over the country making inquiries about the dress and asking for patterns – showing how ready and anxious women were to throw off the burden of long, heavy skirts.” In May of 1851 Amelia Bloomer introduced Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Stanton said, "I liked her immediately and why I did not invite her home to dinner with me I do not know."

The circulation of The Lily rose from 500 per month to 4000 per month because of the dress reform controversy. At the end of 1853, the Bloomers moved to Mount Vernon, Ohio, where Amelia Bloomer continued to edit The Lily, which by then had a national circulation of over 6000. Bloomer sold The Lily in 1854 to Mary Birdsall, because she and her husband Dexter were moving again this time to Council Bluffs, Iowa, where no facilities for publishing the paper were available. She remained a contributing editor for the two years The Lily survived after she sold it.

Labels:

19C,

Biography,

Fashion/Clothing/Dress/Costumes,

Slavery & Servitude,

Women Working,

Women's History,

Women's Rights,

Women's Suffrage

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

+Harpers+Weekley+Decoration+Day,+May+30,+1871.jpg)

+Harpers+Weekley.jpg)

+in+Harpers+Weekley.jpg)